InvestAct investment magazinen.Number 1

What is InvestorAct?

InvestorAct is a completely new kind of investment media publication. Published digitally twice a month, the magazine provides investors with timely, educational, and engaging content that inspires private investors to get interested, improve their skills, and seek new knowledge about investing.

InvestorAct brings global investment topics into clear and accessible English. The purpose of the magazine is that every new issue offers something fresh and diverse. Today, investing is no longer the exclusive domain of those with large amounts of capital or institutions. Anyone can grow their wealth through investing.

By investing, anyone can achieve their goals—whether small or large. Investors can also focus on things they find interesting or where they have more knowledge than others. For example, video game players often know which games are likely to succeed—better than a well-paid investment bank analyst building spreadsheets.

Investors also have the power to make an impact. For example, by buying shares in new technology companies at the time of their IPOs. Investing is diverse, exciting, and educational. These are exactly the things we want to bring to our readers at InvestorAct.

The content of InvestorAct is simple, well explained, and written so that anyone—from experienced investors to complete beginners—can learn and discover new ideas. Our goal is that every issue always includes a few recurring sections, such as stock analysis and a review of the biggest gainers and losers. In addition, each new issue will also contain fresh articles that don’t repeat every time, so readers are always pleasantly surprised when opening InvestorAct.

Welcome to InvestorAct.

In the first issue we cover, among other things:

How and why investors should keep a cool head in turbulent times

An article on African markets and opportunities for investors

A feature on Microcap investing

Three short stock analyses

The Iron ore mining industry

Investment wisdom of the day

The world in turmoil – how should an investor respond?

This year no investor can say it has been an ordinary one. Every investor has read headlines shouting “AI WILL BRING FUTURE RETURNS” or “TRUMP IMPOSES NEW TARIFFS – HOW SHOULD INVESTORS PREPARE?” Even though the year has been turbulent on the markets, the investor should read history and learn what has happened in past hypes and bull markets.

Most often, all the doomsday proclamations on the markets, as well as the rosy predictions—like AI today—follow the same pattern. Toward the end, the proclamations get louder and so does the stock rally. The reason is simple: the big crowd cannot stop celebrating at the right time. Much of this is psychological. The continuous improvement of things year after year, like stock price increases, makes people believe the rise will go on.

This makes people forget perhaps the most important thing in investing: independent thinking. If an investor justifies an investment by saying “AI is the future, therefore I invest,” that is not independent—it is mainstream. The same applies to Trump’s tariffs. Trump is a businessman; he makes deals, changes them, and is ready to negotiate.

The investor must think about his or her own strategy. The most important thing is to have a strategy and clear goals. For some, the goal is to buy a home; for others, financial independence. If you believe you will reach those goals only in 10+ years, you can pay less attention to all these market news—tariffs, AI, interest rates, wars. These are things that constantly change. If you are a trader or a crypto investor, then these matter a lot, since you almost make money directly from the volatility these news create. But if you are a long-term investor, time is on your side. As the father of value investing Benjamin Graham said: “In the short run, the market is a voting machine; in the long run, it is a weighing machine.”

Practical tips for how an investor can respond to market turmoil:

- Limit reading clickbait and sensational news.

- Read carefully company quarterly reports and news about them, and how they comment on current issues and possibilities like tariffs and AI.

- Occasionally check company valuation multiples such as P/E, EV/EBIT, dividend yield, etc. Compare your portfolio companies’ valuations with their listed peers.

- Analyze company growth numbers. Ask yourself: is it realistic that they can achieve these growth expectations, and how will they achieve them?

- Portfolio allocation: Decide how much of your portfolio is in stocks, cash, bonds. Possibly reduce stock weight if you are uncertain about your current investments.

Number 1

he S&P 500 index is currently (29 August 2025) at an all-time high, higher than ever in its history. At the moment it is close to 6,500 points.

The P/E ratio (price relative to earnings) for the “Magnificent Seven” companies—Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Tesla—remains elevated. The S&P 500 median P/E is currently around 27. Without the Magnificent Seven, the rest of the index trades at a P/E of about 20. These are among the highest P/E levels in recent history for the world’s largest companies.

Number 2

The well-known Labubu has caused a huge stock surge for the Chinese toy company Pop Mart, which manufactures it. The company’s stock has risen more than 250% during this year. The toy quickly became a fashion phenomenon, with Hollywood and other celebrities using it.

Time will tell how things will go for the Chinese toy maker, because Labubu has caused a huge demand spike, and the stock’s rise has been based almost entirely on this toy. At the moment, Labubu accounts for about one-third of Pop Mart’s revenue.

Number 3

The well-known super-investor Warren Buffett’s holding company, Berkshire Hathaway, bought 5 million shares of health insurance giant UnitedHealth Group, with a value in Berkshire’s portfolio of about USD 1.5 billion. UnitedHealth represents only about 0.6% of Berkshire’s portfolio, so movements in the stock do not have a major impact on the overall holdings.

The health insurance giant UnitedHealth Group’s stock has dropped significantly, about 50% in the last five months, from around USD 600 to the current USD 300.

Number 4

Novo Nordisk, Denmark’s and the world’s fourth-largest pharmaceutical company, has taken a major hit in the growing weight-loss drug market. Novo’s stock has collapsed about 60% from the June peak, falling from around 1,000 Danish kroner to the current 350 kroner.

The reasons for this include a downgrade of its sales growth forecast from 13–21% to 8–14%. Competition has also intensified as rival Eli Lilly has launched its own weight-loss drug, increasing the battle for customers in this rapidly growing sector. In addition, rising costs, new investments, and a growing workforce have also negatively affected the company.

Number 5

The Helsinki Stock Exchange OMXH Cap GI, the weight-limited index, has risen from 25,365 points in early April to about 30,700 points at the time of writing—an increase of around 20%. It may be possible that at the end of the dark tunnel for the Helsinki market, some light is finally beginning to appear.

Among globally known companies, for example, the technology company Nokia and the game developer Remedy are listed here.

Africa is for many investors an unknown place. This is for good reason. Investing in Africa is difficult. Most brokerage services in Europe or the United States do not offer the possibility to invest there. The reasons include, for example, illiquid markets—African stock exchange trading volumes are small, which makes executing orders very difficult. African exchanges also lack proper infrastructure for broker services to integrate their trading systems so that given orders would go through smoothly.

The yearly total trading volumes of the largest African exchanges in euros are approximately:

Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE): EUR 272 billion

Egyptian Exchange: just under EUR 19 billion

Casablanca Stock Exchange (Morocco): just under EUR 9 billion

For comparison, the Helsinki Stock Exchange has about EUR 105 billion.

From this we see that the Johannesburg Stock Exchange’s trading volume is much larger than Finland’s. The Johannesburg Exchange, i.e. South Africa’s stock market, clearly stands out from the rest because it has a long history, and its trading is largely centered around mining companies.

The Johannesburg Stock Exchange is also the main gateway for foreign money invested into Africa. Most funds that are offered even to retail investors allocate 30–80% of their African holdings to Johannesburg. This itself shows how small the rest of Africa’s markets are compared to other continents.

Also, South Africa’s largest asset manager, the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), with about EUR 140 billion assets under management, invests around 80% of its assets into the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. The reason is simple: as mentioned above, the trading volumes of the other African exchanges are simply too small for large investors.

What about Africans themselves—how do South Africans, Egyptians, Nigerians, and Moroccans invest? Clear data is not available, but in general it is estimated that most Africans do not, and cannot, invest in stocks. The ordinary people in Africa are usually low-income, and if they invest, they buy land or keep their money in the bank.

In South Africa, about 10–15% of the population invests in some way. If the markets are to become safer and more liquid, a good starting point would be for ordinary people or larger institutions to invest more actively in stocks. However, this is not the case in most countries outside of South Africa.

In Africa, according to general information, there are about 100 (maybe a little more) companies worth over USD 1 billion. Around 70 of them are in South Africa, which is explained by the large size of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange and the resulting developed financial system.

Other billion-dollar companies are found in countries such as Egypt, which has about 10–14. Only a small part of these billion-dollar companies are technology firms. There are hardly any listed African technology companies worth over USD 1 billion, and unicorn-level private companies (not listed) number only about 10%.

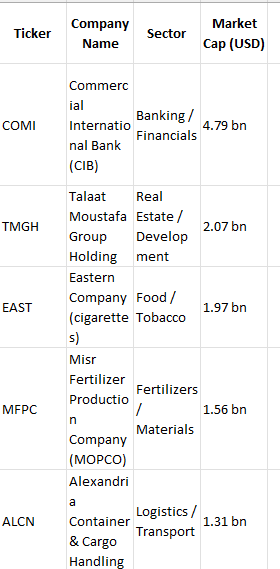

But if one could invest in African companies, and we take Egypt as an example, it would look like this.

As can be seen from the table, traditional sectors dominate among the companies worth more than USD 1 billion. The banking sector, real estate development, and manufacturing industries are common. Credit rating agency Fitch forecasts that the Egyptian economy will grow at about 4.6% annually from 2027 onward. We can assume that the companies shown in the list could reach good revenue growth figures compared to their European and American peers. Assuming we add, for example, 3% on top of the economic growth, this would mean around 8% annual growth for these companies on average.

What about returns? Let’s take two companies for comparison:

- MFPC (Misr Fertilizer Production Company) – fertilizer producer

- TMGH (Talaat Moustafa Group Holding) – real estate development company

MFPC’s total return in Egyptian pounds over the last 5 years has been about 800%. This looks very good—in practice about 50% CAGR. But we must take into account that during the same time the Egyptian pound has lost about two-thirds of its value. With this information, the total return in euros would be a little over 215%, or about 25% CAGR. Even so, this would have significantly outperformed the S&P 500 (16% CAGR) and almost matched the Nasdaq (22% CAGR).

What about the Egyptian stock exchange’s general index (EGX 30)? The return in local currency has been about 210%. At the same time, the Egyptian pound weakened by -65%, which means the total return in euros over 5 years was only 7.6%—about 1.5% CAGR.

In Africa, each country has its own currency, and currency fluctuation risk is large. Here are some examples from the 2000s when currency risk materialized and caused major currency depreciation:

In 2001, the South African rand collapsed by about 40% against the dollar due to political uncertainty.

Between 2016–2023, the Nigerian naira was devalued several times. The reasons were foreign currency shortages and the collapse of oil prices.

If someone had held their wealth in these currencies, the stocks would have had to rise substantially in order for the investment, once converted back into euros, to have been profitable in the end.

Another reason for the weak side of African markets is accounting standards. In many of the developing African countries where stock exchanges are located, the accounting and auditing systems are still far from Western standards. This means that foreign investors may not receive high-quality or even accurate financial statements.

One example of a major accounting fraud is the South African conglomerate Steinhoff. The scandal was based on the company inflating profits and balance sheet values. In the end, it was revealed that Steinhoff had reported over EUR 6 billion in fictitious revenues. The stock price collapsed by more than 85% within a week. Later, the company recorded impairments of more than EUR 12 billion. Considering that Steinhoff was a large company, and such a big fraud still happened, the risk that a smaller company might manipulate its numbers could be even higher.

Sector distribution – The industry split of many African stock exchanges is usually concentrated in oil & natural resources, construction, and basic manufacturing. Most companies operate only locally and do not have international expansion ambitions. Another risk that local companies face is macroeconomic weakness. For example, in construction, many African companies depend heavily on government support and government-initiated infrastructure projects. Naturally, if the economy falls into recession, and for example if global oil prices decline, this would directly affect certain sectors.

There has, however, also been positive development in African stock exchanges. The Ethiopian Stock Exchange is reopening—it was last open in the 1960s–70s. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange’s trading volumes have grown in the last two years. The exchange has also invested in data analytics technology to help brokers improve their trading. In Nigeria, the foreign investor share of trading rose from about 21% at the end of 2024 to June 27, 2025.

Whether one thinks African markets are good or bad, every Western retail investor has the possibility to allocate part of their portfolio to African stocks. The easiest and simplest way is through ETFs. One such fund is the Vanguard FTSE Africa Index Fund ETF, with about EUR 2.5 billion AUM, investing in about 40 of the largest African companies, including holdings in Nigeria and Johannesburg.

Another broader option is the VanEck Africa Index ETF. The difference with Vanguard is that VanEck invests not only in African-listed companies but also in companies outside Africa that derive more than 50% of their revenues from Africa. This is interesting for investors because these companies may operate in more diversified industries than purely African-listed firms.

In the end, Africa’s role in the global economy will almost certainly grow in the future, so a rational investor should at least study the investment opportunities in African markets.

Chipotle Mexican Grill is a surprising name among significantly declining stocks, but this is still the case. The stock fell about 26% between July 3 and August 28. Chipotle is known as a company with strong competitive advantages and brand power, and it has grown earnings in the last 5 years at a 43% CAGR.

The main reason for the significant share price decline was the Q2 earnings release. The company met analyst targets, but investors were concerned about the slowing same-store sales growth. In recent years, the company has suffered from inflationary pressures and the resulting weakening of consumer purchasing power.

Chipotle has in recent years invested heavily in digital ordering, which accounted for 35.5% of sales in Q2. The company has also built its ordering business successfully, reaching about 20 million active loyal users.

Adobe is one of those companies that investors have long considered indestructible. Adobe’s business model, subscription-based billing, and its digital content creation software—such as photo editing tools—have been critical tools for businesses. This has supported Adobe’s 70%+ gross margins.

Adobe’s stock fell more than 16% between June 19 and August 28. That is not yet massive, but if we take a longer-term view from February 2, 2024, to August 28, 2025, the stock price has declined about 45%, from USD 635 to USD 350.

Key reasons for this decline have been growing competition, for example the rise of Figma, and the growing impact of AI in the field. More and more often, AI can now create image edits or generate images simply by writing a prompt. This has created a new risk to the durability of Adobe’s business model. The main question is: is Adobe still an essential service, or can AI now do what previously required Adobe’s software?

Even though many concerns are swirling around Adobe, they have not affected Adobe’s key business metrics, namely revenue growth. It has been about 10% year-on-year for the last three years.

At the moment, the key question for Adobe should be whether it can make the necessary AI investments. While others are making similar AI investments, can Adobe integrate AI into its services and develop new paid services around AI?

Robinhood Markets is one of the stock brokerages that has changed the trading industry. Robinhood has quickly grown into a service with over 26 million users. Its market share in the latest Q2 was about 6.5%.

Robinhood has challenged the larger brokerages and has succeeded especially because the app looks much more like a social media service, and it has been simple for beginner investors to use.

Robinhood’s stock rose about 200% between April 8 and August 29. The reasons for this include that Robinhood aims to become a one-stop platform for all investing—cryptocurrencies, tokenization of stocks, and wealth management.

Robinhood has acquired the significant Belgian crypto exchange Bitstamp and the U.S. wealth management platform company TradePMR. It also wants to expand its platform usability to the EU area, where it is applying for a crypto asset regulation license (MiCA).

Robinhood’s active growth strategy has been especially visible in its assets under management (AUM). These grew from USD 193 billion in 2024 to USD 279 billion in Q2 2025.

In Summary

Chipotle

Slowing same-store sales growth and inflationary pressures could hinder the achievement of growth objectives.

Chipotle has pricing power, and its business is very resilient to worsening economic conditions because the product it sells, Mexican food, is something that people consume daily.

Adobe

AI is revolutionizing the image processing and editing industry. For Adobe, the number one question in its business, and among investors excited about artificial intelligence, is: How is Adobe implementing its AI strategy? And how does Adobe plan to respond to the trendiest AI image processing companies, such as Figma, and a host of other AI-developing companies' products?

Adobe's existing cash flow is strong, and corporations already use their products widely. Adobe can easily invest in AI tools that will be as good as, and most likely better than, any of their competitors' products.

Robinhood

Robinhood is making many moves by expanding into crypto, acquiring other money management companies, and launching credit cards. This may be a good strategy. However, Robinhood is moving very quickly, and if something goes wrong, it could expose investors to certain risks.

Robinhood is trying to become an all-in-one platform for private investors. If it succeeds, this could bring significant rewards to shareholders.

Microcap investing is for a skilled small investor often the most profitable way to invest, but for a less experienced investor it is often the most risky way to invest. Simply, microcap companies are companies valued under USD 300 million, which are small for one of two reasons.

1.They are new companies that have listed as small firms.

2.They were large-cap or mid-cap companies earlier (over USD 1 billion companies), but for some reason their share prices collapsed.

It must always be kept in mind that when analyzing microcap companies, 95%+ are basically junk. The companies are either zombies, meaning they do not have a clear strategy, product, or even enough capable employees to build a business. Some are resource or early-stage junior mining companies that are developing what they believe is a promising mining prospect.

The majority of mining juniors never get a mine into production, because permits are hard to obtain, and the profitability of the mine depends almost entirely on drilling results. If drilling results suddenly weaken, then practically the company’s days are numbered. If the mine is finally established, which can take 7–10 years, it requires numerous share issues, and the investor’s money often runs out by that stage.

A small part of microcap companies are, on the other hand, gold mines. These companies share a few similarities:

1.Niche market. The company brings a new product to a relatively small market and captures that market. Even if the market is small in monetary terms, if it is captured, it can be extremely profitable for shareholders.

2.The company gains wider investor attention. A microcap company may at first just be a decent small company growing at a normal pace. It does not necessarily need to be a high-growth company. But its multiples, for example the P/E ratio, can be very low. For example, imagine a company that grows 8% per year, has a high-quality product, and no major visible risks to its business. It trades at a P/E of 5. It could reasonably trade at a P/E of 10. This would mean that an investor could gain 100% return immediately if the P/E doubled. For this to happen, either

a. retail investors discover the company and agree that the P/E should be 10, or

b. an acquirer makes a takeover offer for the company at P/E 10.

3.Market rotation toward small caps. When market focus shifts to small caps (larger than microcaps), usually the price of almost any company in that category can rise if more capital flows into that market. The same happens if a certain sector, for example artificial intelligence, is in fashion. Some microcap AI companies, even those without a real product, have sometimes risen hundreds or even thousands of percent only due to the hype around AI.

Most often you cannot use a buy-and-hold strategy with microcap companies. The company must be constantly monitored. For example, if a key person or visionary leaves, it may be best to sell the company immediately, even if at that moment it seems to have a bright future. This is because most often microcap companies live on one visionary. The founder in the early stage is the most important asset of the company.

This is one of the most difficult things to analyze when investing in early-stage growth microcaps. Normally, when investing, an investor can study past growth numbers, markets, and customers. But when investing in microcaps, one must analyze the founder’s vision, intelligence, the feasibility of the product, and his or her character. These are often the hardest, if not the most impossible, things to evaluate when investing.

This also makes microcap investing sometimes risk investing, because out of 10 investments, maybe only one succeeds. But if that one succeeds properly, it will more than compensate for the losses of the other nine.

Some of today’s largest and most successful companies were once microcaps. Today’s biggest company, Nvidia, was a microcap when it listed. When Nvidia went public on 22 January 1999, it had a market capitalization of about USD 626 million. At the time, it already had several successful products, and in the same year it launched the GeForce 256, the first GPU, which was the beginning of Nvidia’s success. Nvidia’s total return from that time until today has been over 350,000%.

Another example is Monster Beverage (Monster Energy Drink). These companies represent the other extreme—the ones that managed to capture an entire market. Investors are often convinced by the huge potential of such companies, often advertised with flashy and colorful investor presentations. Most of the time, an investor should remove these dreams from their head. The probability of finding exactly these companies that will change the world is very low.

Even if investors did find these companies and invested in them for the long term, the journey would be very bumpy. During the dot-com bubble, Nvidia’s stock collapsed from its 2001 peak of about USD 23 (split-adjusted) to USD 2.5 in October 2002, an 85% drop. During the financial crisis, there was another 80% drop. The same pattern repeats with nearly all of the best-performing companies. Their investment story is constantly challenged. Fast growth expectations drive the share price up, and suddenly some economic downturn or sector weakness scares investors away, and the stock collapses by 80% seemingly out of nowhere.

Depending on the investment strategy, there are some general rules of thumb that microcap investors often follow:

1.Key executives leave.

2. Competition changes significantly – a bigger and richer player enters the market, so the company can no longer compete with product quality, distribution, etc.

3. The company takes on a lot of debt.

4. The company makes too large of an acquisition.

5. The company diversifies into too many products, expanding the business too much.

6.The company’s value has increased significantly, by 200–1000%. It may be time to cut back part of the investment. This point is a broader topic to be discussed further, but for now it is mentioned here.

Iron ore mining is a well-known industry, but, for example, a European iron ore producer is not the same as an Indonesian iron ore producer. The export countries they serve have very different economic growth outlooks—for instance, low-growth European economies versus faster-growing Asian economies. In Asia, there is generally higher demand and, in many countries, lower labor and overall cost structures compared to Europe.

Demand for iron ore is steady, and the long-term prospects are good because of urbanization and rising living standards, especially in Africa and Asia. Iron ore production, processing, and end products are often very important for many national economies.

Australia is the world’s largest exporter of iron ore, accounting for over half (around 55%) of global exports. After Australia, the largest producers are Brazil (~440 Mt), China (~270 Mt), India (~270 Mt), and Russia (~91 Mt).

In 2023, the global iron ore mining market was valued at about USD 279 billion, and by 2032 it is expected to grow to nearly USD 400 billion. This shows the industry is steadily expanding. Geographically, an investor interested in iron ore producers has the opportunity to diversify by choosing among several countries as investment targets.

Iron ore is, with other ores, a commodity product. So the product is very competitive, and all mining companies usually have to compete on price. On the other hand, the location of the mine close to the selling market, and the large size of the mine which can bring economies of scale, affect the profitability of the mine.

Iron ore price fluctuates heavily according to demand and supply. In the bad case, a mining company has made at the peak of the cycle expensive investments with debt money into new mines at high prices. Then, when the economy has started to weaken again, the mining company has got into trouble, with weakened demand and large losses. One example is African Minerals, which had a big mining project in Sierra Leone. In 2015 it was put into bankruptcy because of insolvency. This was also affected by the fall of the iron ore price.

It must always be noted when considering investing in iron ore companies. One must choose if investing into a few big companies: Vale SA, BHP, Rio Tinto, ArcelorMittal, Fortescue Metals Group, and Anglo American. Then there are only pure play iron ore producers: Fortescue, Champion Iron, Grange Resources, and Ferrexpo. Except for Ferrexpo, there is also Champion Iron, whose mine is located in Québec, Canada, but the company itself is Australian.

There is some choice, but how have they performed. Vale SA +260%, Rio Tinto +180%, BHP Group +150%, ArcelorMittal +180%, Fortescue +1000%, Anglo American (from the 2016 bottom) +900%. Grange Resources about +100%, Champion Iron +2300%, Ferrexpo around ±0%.

So we see that good returns have been made during the last ten years. Especially Champion Iron and Fortescue have been particularly profitable. Reasons for this include that they are pure play iron ore producers, meaning their whole business is optimized for iron ore production. Then they can operate the business better and grow according to different demand situations. Unlike others like BHP, Rio Tinto, and Anglo American which produce many different minerals. In that case, they cannot focus as well on one business segment, and they also must choose between several different segments where to invest. Fortescue and Champion do not have this problem. They either reinvest in new iron ore deposits or distribute profits to shareholders as dividends.

Behind Champion’s strong return is also the fact that in 2016 it bought a mining project in Canada. In 2018 it shipped the first batch of ore. Since then it has grown. So one successful mining project is behind all of Champion’s returns. This is also one way to make money—by buying shares in early-stage mining companies with a promising project, but no operating mine or permits yet. If the mine is successfully started, the returns can be astronomical.

One company can be taken into closer review, Fortescue. In addition to its iron ore mines, Fortescue owns a large logistics chain. It owns about 760 kilometers of railway network which connects its mines to the port. It also owns eight ore transport ships, and operates its own berth and cargo handling infrastructure.

Unlike most other companies, it takes the green transition and zero emissions seriously. Fortescue has a target to build 2–3 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity, mainly solar power, with the goal to power its operations with green energy. Fortescue also invests in green hydrogen production in several countries. This is exactly what separates Fortescue from other mining companies. It wants to diversify its business from only iron ore mining into more broadly transforming the steel industry with green hydrogen and green ammonia. By investing in these, it creates production capacity and technologies that will be used more and more in the future. Even this alone is promising for an investor.

Then we can look at the financial data. Fortescue is a cash flow machine. Last year it generated about USD 2.6 billion of free cash flow. Over the last 20 years it has returned around USD 42 billion to shareholders in dividends.

Another very interesting thing is Fortescue’s cost structure. Its Hematite C1 cost is about USD 17.99 per wet metric tonne. This is one of the best in the industry. This means that for every tonne of iron ore mined, all direct cash costs—mining, processing, rail, and port loading to the ship—are about USD 18.

If iron ore is sold for USD 100, then about USD 18 is subtracted. After that, the iron ore quality is considered—how much iron content the ore has. If it is not the same quality as the benchmark, the price is adjusted. After this, the margin that remains before taxes and possible royalties is about USD 40–50 per tonne.

Fortescue also has a strong balance sheet, with about USD 4.3 billion in cash and USD 1.1 billion in net debt. Its gross debt to EBITDA is 0.7 times.

So for an investor interested in iron ore mining companies, Fortescue is definitely worth considering.

Assessing the current stage of the economic cycle is important for the total return. If you do not analyze the cycle at all, it might not matter even if the ore producer increases production in the future and it would be profitable. The current stock price has the biggest effect on the total return that the investor gets from the company.

For example, the economic cycles and price fluctuations in the 2000s that affected the iron ore price:

1.After the pandemic, stimulus policy pushed the iron ore price to around USD 200 per tonne in July 2021. Since then, the price has declined, reaching about USD 100 per tonne in mid-2023.

1.In the early 2000s, iron ore was about USD 25 per tonne. After that, there was a significant seven-year upcycle where iron ore peaked at about USD 200 per tonne in 2008. Then came the global financial crisis, and the price collapsed to about USD 60 per tonne in early 2009. At the peak, iron ore had delivered roughly 700% gains, but this collapsed by nearly 100%. The same happened with the shares of several major mining companies, which fell between 50% and 80%.

The reason for this strong economic growth and the supercycle in iron ore and other commodities was among others globalization, when China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, and China’s massive construction and industrialization boom, which significantly increased iron ore demand.

Today, China is still a major iron ore producer, and by far the largest importer of iron ore in the world. China’s strong economic growth in the 2000s also had a major influence on iron ore prices.

Iron ore price has fluctuated in the last 10 years between USD 25–200 per tonne. At the moment, on 30 August 2025, the price is around USD 100.

What are then the forecasts and current views on iron ore? Mainly, the outlook for the next few years is weak. Prices are expected to even fall to around USD 80–90 per tonne next year. This has been affected by the weaker global economic situation and also by Rio Tinto investing in and opening a large mine, the Western Range project in the Pilbara region of Australia, targeting about 25 million tonnes per year. Rio Tinto also has a wider USD 13 billion investment program in Pilbara. However, these mainly replace aging mines that are reaching the end of their life.

Another large new project is Rio Tinto’s Simandou iron ore project in Guinea, Africa. The total planned production capacity is aimed at about 60 million tonnes by 2028.

The general forecast at the moment is that iron ore production will exceed demand at least in 2026–2028. According to some estimates, these years could see even up to a 200 Mt surplus of iron ore.

So investors should note that the supply/demand balance is against investors right now. But for investors looking at years beyond 2028, it could make sense to analyze mining companies like Rio Tinto, which are opening large mines and would be the biggest beneficiaries if the iron ore price stabilizes in later years. On the other hand, smaller mining companies may be in a weaker position if they have a mine planned to start in the coming years while prices remain low.

How should an investor try to forecast the iron ore price, and through that decide which mining company to invest in?

- China – the outlook of China’s economy. If the Chinese housing market turns to a better direction and construction activity picks up, it would give a positive boost to iron ore demand and create confidence among investors that the worst of the price collapse is already over. China, for example, has launched a stabilization fund of about 2 trillion yuan (around EUR 240 billion) aimed at financing unfinished projects, reducing excess inventory, and improving the payment ability of property developers.

- United States infrastructure investments. In the U.S., the road network, electricity grid, water pipelines, and other infrastructure are becoming critically old. For example, many major highways are more than 50 years old. So at some point, the government must increase infrastructure investments. Current estimates for 2024–2034 suggest that total required investments would be over USD 9.1 trillion. At the moment, public and private funding is expected to reach about USD 5.4 trillion. One of the major infrastructure packages passed earlier by the Biden administration was the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act (IIJA), which provides about USD 1.2 trillion of additional investments. These major needs must be met during the next 10 years. This would mean growing demand for steel, and through that for iron ore, in the United States. Looking at the current “America First” rhetoric of the administration, one could expect that because of tariffs, U.S.-produced iron ore would be in strong demand. So American mining companies and those oriented toward the U.S. market could benefit.

3.India. India is also a large iron ore producer. It has large reserves and currently already big mines and proven resources. India produces about 290 Mt of iron ore, and its estimated total reserves are about 30 billion tonnes. India’s target is to raise total production to 425–430 Mt.

India’s growing economy requires a lot of steel, and the iron ore needed for that. India has aimed for its steel industry to source the required iron ore domestically, and so far it has been able to do so. The Indian government has also planned that about 80% of its iron ore should be processed further to raise the Fe content to around 62%.

In the future, demand for iron ore in India may rise so much that it might need to import as much as 100 Mt of iron ore from abroad. This is exactly one of the things from which foreign, especially Australian, mining companies could benefit. For green steel production, the required ore quality should be about Fe 65–67%. So for green steel production, imported high-grade ore would be needed.

4. For green steel production, high-quality iron ore with about Fe 65% is needed in order to make production simpler. Mining companies that have mines producing the required grade of iron ore can receive a significantly higher price for the ore sold—sometimes USD 10–20 more per tonne. For example, Rio Tinto’s Simandou project in Guinea is expected to produce the high-quality ore required for green steel. This is one reason why Rio Tinto is investing there now.

The green steel market is currently about USD 7 billion and is forecasted to grow, depending on the source, to USD 50–130 billion. This also depends on how fast the necessary hydrogen and renewable technologies can be developed and scaled up so that they are economically viable in industrial production. In this area, Fortescue is also advancing the progress of the entire industry with its green energy investments. In this way, it can also benefit from higher iron ore selling prices if green steel becomes a major success.

In the end, the iron ore industry is large and will continue to grow. Mining companies are actively investing in new mines with higher iron content and also in green energy.

We all have been there, at least most of us. Stock price goes down 10–20% a day. Business showed one bad quarter, capable management explained all, nothing really bad happened. Every investor must know that. Most of the time stock goes down because of seemingly bad business development. We react to something that management knew months ago. And they have already extinguished the fire. This happens all the time to stocks that are hyped. If investor wants to avoid those big drops, the investor must, before making an investment decision, think about how much expectations have been priced into this company’s stock. A small setback or failure in the company’s business is always a positive thing. Because then it is seen how well customer relationships have been built, investments invested, and how realistically management’s growth expectations were justified.

Most often the selling wave that targets the stock when the company’s matters go worse is strong. Investors also strengthen the selling wave when media takes the issue on a stick, and the same message about the company spreads to several respected newspapers, and analysts start lowering target prices and giving sell recommendations. So basically, a large part of that selling wave and the reasons why investors sell are no longer based on the company’s problems but on the fact that other investors are selling.

These target price investors do not think very independently about the business but base the investment decision on target prices and sell recommendations. Many investors claim that they are not such investors but independently thinking investors. That is usually true. But when an investor sells an investment in a falling stock, he quickly concludes with first-level thinking that the stock should be sold, even though in practice he is modeling himself after the target price investor.

One of the commonly stated rules of investing is: invest where others do not invest. This is exactly the core of investing. That is, investing in a new AI startup where, with 100% certainty, you will lose a large part of the investment if the goals are not met. There are companies that have no expectations directed at them. Investors have abandoned them, often for good reasons — results have disappointed, poor strategic decisions have been made, and product launches have failed. But investors must understand that companies are like ships. Some ships, for one reason or another, sail into a storm. But if the ship is made of strong wood and has a somewhat competent captain, that ship will survive the storm and succeed in the future. Investors must consider which companies have a strong enough hull to survive the storms.